Prices triple, triggering a scramble; ‘Could be a health risk’

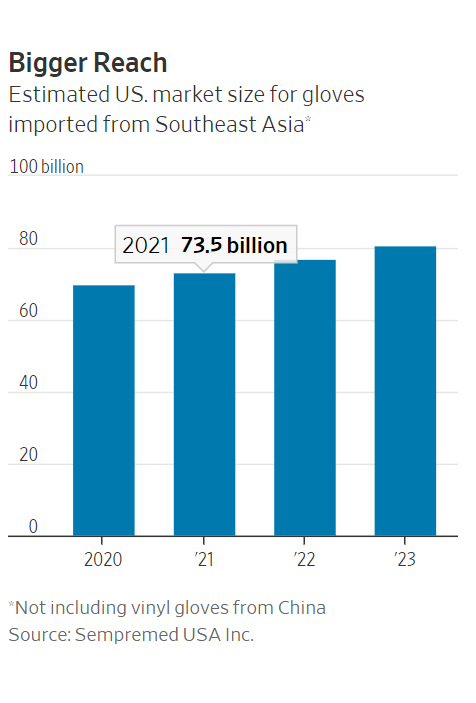

The U.S. imports around 70 billion nitrile gloves annually, mostly from Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand.

PHOTO: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG NEWS

Brokers are peddling counterfeit medical gloves as a shortage of this critical commodity has tripled prices during the pandemic and pinched front-line and other workers as schools and businesses reopen.

In recent weeks, companies employing front-line workers have bought fake versions of “nitrile,” or synthetic rubber gloves, sold in boxes labeled “examination grade,” posing potential health risks, according to glove distributors and manufacturers.

Examination-grade gloves made of synthetic and natural rubber are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and provide greater protection and durability than vinyl gloves, which can break down and don’t guard against certain chemicals, glove manufacturers say.

An FDA spokesman said the agency couldn’t quantify the number of counterfeits, saying it works with manufacturers and U.S. Customs to intercept gloves that don’t meet government standards and publishes a list of foreign manufacturers and shippers that produce gloves of subpar quality.

Most nitrile gloves are made in Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand, with the U.S. importing around 70 billion annually. Several large manufacturers have warned customers about fraudulent gloves and the Malaysian Rubber Glove Manufacturers Association said it had received more than a dozen reports from members about “frauds and fake agents” seeking to sell gloves, in some cases producing fraudulent letters from the glove manufacturers.

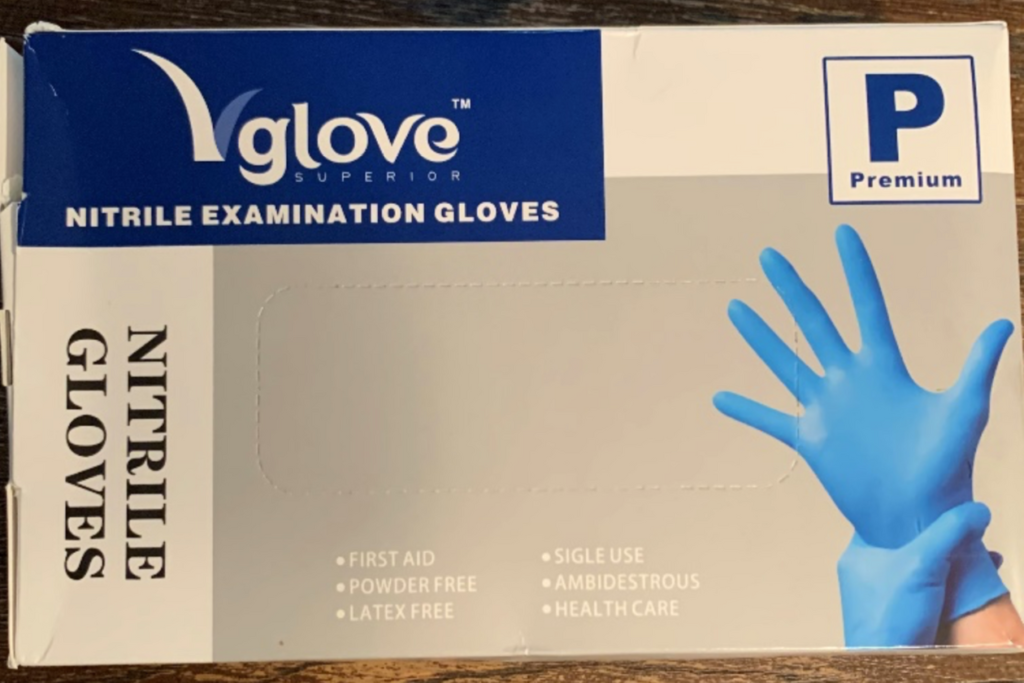

Late last month, Dan Grinberg, CEO of glove importer Elara Brands, emailed his sales force warning of counterfeit gloves with misleading boxes lacking key information such as origin and quantity. He said a customer had bought bogus gloves labeled as nitrile made by Vglove, a large Vietnamese manufacturer, which “could be a health risk.”

VRG Khai Hoan, the Vietnamese glove manufacturer that produces Vglove brand nitrile gloves, issued a statement to customers recently warning of such counterfeit versions of its nitrile gloves and fraudulent activity by people impersonating brokers of the company. It said they use counterfeit signatures and boxes with phony labels.

The company reiterated its warning about fraudulent activity in an emailed response to The Wall Street Journal to questions about counterfeit activity involving its brand.

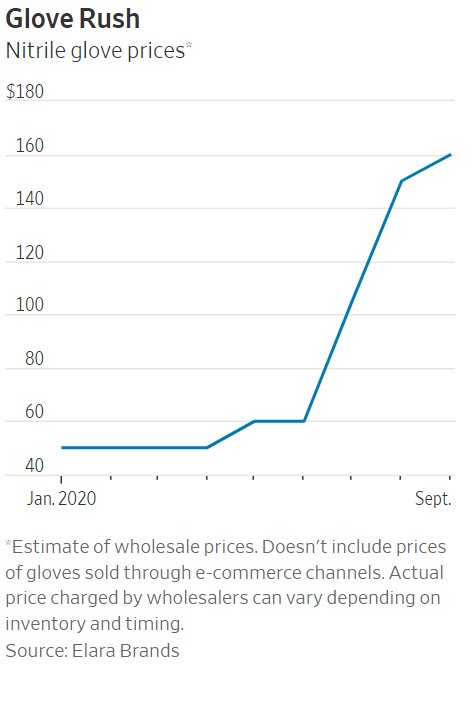

Prices for the gloves have soared amid heightened demand and short supply and a flood of new entrants have moved into the market for gloves, creating a scramble by buyers and sellers for supplies.

There is no concrete data on glove prices, but glove distributors and manufacturers say prices have surged amid continuing waves of Covid-19 infections around the U.S., jumping to as much as $15 for a box of 100 gloves, from around $4 a box.

Since mid-July, supply has been further constricted after the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency banned imports of gloves from the world’s largest glove manufacturer, Malaysia’s Top Glove Corp. BHd, which produces 1.7 billion gloves imported into the U.S. each month, according to the company.

A spokesman for U.S. Customs said the agency took the action because of “reasonable evidence of forced labor in the manufacturing process,” at Top Glove plants in Malaysia, adding that CBP has been looking into such concerns since 2019.

Top Glove said in a statement it has begun taking steps to rectify the situation, including remediation payments to its migrant workers, and that it is working to resolve the CBP matter.

In the wake of the U.S. customs ban, shipping containers filled with gloves manufactured by Top Glove have been flagged at U.S. ports, causing their products to be diverted to warehouses where they will sit until the ban is lifted or they are sent back overseas, managers of glove companies say.

Meanwhile, supplies are running dangerously low at some hospitals and businesses that are required to wear the protective gear, state officials and importers say.

Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck, N.J., uses 300,000 gloves a month and meeting that demand has gotten harder in recent weeks, said Don Ecker, executive director of supply chain for the acute-care hospital.

Glove distributors and manufacturers say prices have jumped to as much as $15 for a box of 100 gloves, from around $4 a box.

PHOTO: ELARA

He said Holy Name now pays triple the amount for gloves than before the pandemic. He said supply “has dropped off the face of the earth” and demand “has gone through the roof.”

It’s not just the health-care industry. “Now everybody is taking everything. You’ve got businesses, you’ve got schools,” Mr. Ecker said.

Henrico County in Virginia is scrambling to find gloves as schools and businesses reopen, said Jackson Baynard, the county’s emergency manager. “We are literally buying whatever gloves we can get our hands on that meet our standards,” he said.

The number of needed gloves is enormous because they must be discarded after each use, and front-line workers typically use several pairs each day. Pinching the market further are new users, such as schools and businesses that are seeking glove supplies as they reopen, competing with traditional users like health care workers and food-service employees.

In early July, suppliers told Elie Levy, a Seattle dermatologist, that they were diverting gloves to hospitals where staffs expect a rise in coronavirus infections in the fall.

“We’re adjusting,” he said. “We’re using gloves longer. We’re using anything we can get our hands on.”

Amid the squeeze, there have been canceled orders and stricter terms for glove purchases. After the cancellation of orders for 30 million gloves, Mr. Grinberg said some glove makers told him gloves were available, but only at ever-higher prices.

Unlike the early days of the crisis, when states and other buyers were willing to put money down upfront for protective gear, brokers now are required to put up money themselves to procure glove shipments.

In May, Princeton, N.J., entrepreneur Kyle Kane secured a weekly supply of two million boxes of gloves from Vietnam manufacturers. But he quickly discovered that Western buyers were wary of paying a nonrefundable deposit for inventory they couldn’t inspect, while Eastern manufacturers wouldn’t make gloves without a deposit.

Mr. Kane attracted U.S. investors to assume the risk of shipping gloves from Vietnam to the U.S., where clients could release escrow payment upon positive inspection. Mr. Kane and his partner since then bought a stripped-down factory in Hanoi, which they are fashioning into a glove manufacturer at a cost of several million dollars.

The factory is scheduled to soon begin production with a capacity to produce 60 million boxes of gloves a month.

Said Mr. Kane: “We needed to take control of our own supply chain.”